Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr., 93, who became the 38th president of the United States as a result of some of the most extraordinary events in U.S. history and sought to restore the nation's confidence in the basic institutions of government, has died. His wife, Betty, reported the death in a statement last night.

"My family joins me in sharing the difficult news that Gerald Ford, our beloved husband, father, grandfather and great grandfather has passed away at 93 years of age," Betty Ford said in a brief statement issued from her husband's office in Rancho Mirage, Calif. "His life was filled with love of God, his family and his country." Ford died at 6:45 p.m. Tuesday (PST) at his home in Rancho Mirage, about 130 miles east of Los Angeles, his office said. No cause of death was given. Ford had battled pneumonia in January and underwent two heart treatments -- including an angioplasty -- in August at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Ford died at 6:45 p.m. Tuesday (PST) at his home in Rancho Mirage, about 130 miles east of Los Angeles, his office said. No cause of death was given. Ford had battled pneumonia in January and underwent two heart treatments -- including an angioplasty -- in August at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Funeral services will take place in Washington and Grand Rapids, Mich., his boyhood home, the Associated Press reported, and public viewings will be held in California, Washington and Grand Rapids. Details had not been announced as of this morning.

President Bush was notified of Ford's death shortly before 11 p.m., at his ranch in Crawford, Tex., the White House said. He called Betty Ford to offer his condolences.

"For a nation that needed healing, and for an office that needed a calm and steady hand, Gerald Ford came along when we needed him most," Bush said this morning. He praised Ford's integrity and "great rectitude" and said the nation will always be grateful for his service.

Vice President Cheney, who served as Ford's chief of staff in the White House, said Ford "embodied the best values of a great generation: decency, integrity, and devotion to duty."

"When he left office, he had restored public trust in the presidency," Cheney said in a statement, "and the nation once again looked to the future with confidence and faith."

The Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum announced extended lobby hours so people could sign condolence books. Messages of sympathy, and donations to a memorial fund, can also be made online.

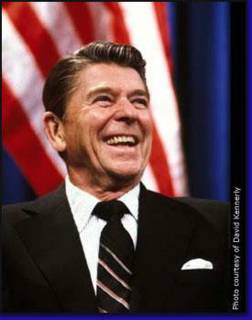

Ford was the longest-living ex-president, followed by Ronald Reagan, who also died at 93. Former first lady Nancy Reagan remembered him in a statement as "a dear friend and close political ally" of the Reagans, praising him for speaking out "on issues important to us all" and for his early support of stem cell research, the AP said.

Ford was the only occupant of the White House never elected either to the presidency or the vice presidency. A former Republican congressman from Grand Rapids, he always claimed that his highest ambition was to be speaker of the House of Representatives. He had declined opportunities to run for the Senate and for governor of Michigan.

He had become vice president Dec. 6, 1973, two months after Spiro T. Agnew pleaded no contest to a tax evasion charge and resigned from the nation's second-highest office. The former Maryland governor was under investigation for accepting bribes and kickbacks.

Ford was sworn in as president on Aug. 9, 1974, when Richard M. Nixon resigned as a result of the Watergate scandal.

"My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over," Ford said in his inaugural address.

"I believe that truth is the glue that holds government together, not only our government, but civilization itself. That bond, though strained, is unbroken at home and abroad."

In the 2 1/2 years of his presidency, Ford ended the U.S. involvement in the war in Vietnam, helped mediate a cease-fire agreement between Israel and Egypt, signed the Helsinki human rights convention with the Soviet Union and traveled to Vladivostok in the Soviet Far East to sign an arms limitation agreement with Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet president.

Ford also sent the Marines to free the crew of the Mayaguez, a U.S. merchant vessel that was captured by Cambodian communists.

On the domestic front, he faced some of the most difficult economic conditions since the Great Depression, with the inflation rate approaching 12 percent. Chronic energy shortages and price increases produced long lines and angry citizens at gas pumps. In the field of civil rights, the sense of optimism that had characterized the 1960s had been replaced by an increasing sense of alienation, particularly in inner cities. The new president also faced a political landscape in which Democrats held large majorities in both the House and the Senate.

But Ford's overriding priority was ending the constitutional and political crisis known as Watergate. It had begun June 17, 1972, when five operatives of Nixon's reelection campaign were caught breaking into Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate office building.

The White House denied any involvement. But as the situation unfolded, the central question was whether Nixon had tried to obstruct the subsequent investigation. A special prosecutor sought answers on tapes Nixon had made of his Oval Office conversations.

The president resisted turning them over on the ground that this would violate executive privilege, but in July 1974, a unanimous Supreme Court ruled against him. Within days, prosecutors found a tape on which Nixon apparently ordered a coverup. The House judiciary committee approved three articles of impeachment. Faced with the virtual certainty of a trial by the Senate, Nixon resigned.

Ford said he believed that his signal achievement was healing the national divisiveness caused by the "poisonous wounds" of Watergate, as he put it in his inaugural speech. "There is no question that this is the thing I contributed," Ford said 30 years later, in an Aug. 25, 2004, interview with The Washington Post at his summer home in Beaver Creek, Colo.

When he assumed office, Ford immediately made clear his intention to change what historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. called "the imperial presidency."

He was "acutely aware," he said in his inaugural address, that he had not been elected to the position he held, and he asked Americans "to confirm me as your president with your prayers." He said he had neither sought the presidency nor made any "secret promises" to attain it.

"In all my public and private acts as your president, I expect to follow my instincts of openness and candor with full confidence that honesty is always the best policy at hand. . . .

"Our Constitution works; our great republic is a government of laws and not of men. Here the people rule. But there is a higher power, by whatever name we honor Him, who ordains not only righteousness but love, not only justice but mercy.

"As we bind up the internal wounds of Watergate, more painful and more poisonous than those of foreign wars, let us restore the golden rule to our political process and let brotherly love purge our hearts of suspicion and hate."

A new spirit was soon evident in the nation's leadership. The Oval Office, long a fortress for an embittered president who frequently fled its confines to his homes in San Clemente, Calif., or Key Biscayne, Fla., was thrown open to members of Congress, old friends, public officials and reporters.

The president's approval rating reached 71 percent. He was photographed making his own breakfast. He was freely contradicted by his eldest son, and his aides said what was on their minds without waiting for official clearance. In the press office, he appointed Jerald F. terHorst, a respected Washington correspondent, as his chief spokesman.

This euphoric honeymoon lasted precisely one month.

On Sept. 8, Ford granted Nixon a full pardon for all federal crimes he had "committed or may have committed" when he was in the White House. The only acknowledgement he received in return was a six-paragraph statement from Nixon in San Clemente saying that "I can see clearly now . . . that I was wrong in not acting more decisively and more forthrightly in dealing with Watergate, particularly when it reached the stage of judicial proceedings and grew from a political scandal into a national tragedy."

Ford said the pardon was necessary to bring Watergate to a close, that he would have had to pardon Nixon sometime in any case and that it was easier to do it sooner than later.

The response was a tidal wave of criticism. Every opinion poll showed a large majority of Americans opposed the pardon. It was denounced in Congress, including by members of Ford's own party. Republican officials gloomily and accurately forecast that it had reintroduced the Watergate issue into the 1974 elections, which proved to be a Democratic landslide. TerHorst resigned in protest.

It was widely assumed that Ford had doomed his political career. By January 1975, his approval rating had plummeted to 36 percent. Not even two assassination attempts, both in California in 1975, generated significant popular support.

The consequences included a three-month delay in confirmation of Ford's choice of former governor Nelson A. Rockefeller of New York as vice president. In congressional hearings, it was disclosed that Rockefeller had made large private gifts to employees on the New York state payroll and that he had played a hidden role in financing a campaign book against Democratic gubernatorial nominee Arthur Goldberg. The disclosures undermined his ability to play an influential role in the Ford administration.

Many conservative Republicans in Congress joined Democrats in opposing Ford's programs. In mid-1975, Gov. Ronald Reagan of California, the darling of the right wing of the GOP, announced his intention to seek the Republican presidential nomination in 1976.

Ford beat back the Reagan challenge, but he narrowly lost the general election in November 1976 to the Democratic candidate, former governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia.

Asked in his 2004 interview with The Post whether the pardon had hurt him in the 1976 election, Ford replied, "It probably did. It was a close election, as you know. . . . There is a group of bitter people who never forgave me and probably voted against me, and the net result is that they probably helped that I didn't win."

Ford closed strongly against Carter after trailing by as much as 30 points in the polls but was damaged by asserting during a debate that Poland was not under Soviet domination. Against the advice of aides who told him this was a blunder, Ford stubbornly waited several days before correcting himself. The impression of bumbling was exacerbated by reports of his purported clumsiness. During a trip to Austria, he tripped and fell while leaving Air Force One, and there were several photographs of him falling while skiing.

But Carter began his own term with a graceful tribute that stands as the general assessment of the Ford presidency: "For myself and for our nation," he said in his inaugural address, "I want to thank my predecessor for all he has done to heal our land."

Throughout his years in Washington, Ford had a reputation for hard work, patience and self-confidence. These qualities gained him a place in the inner circles of the Congress. He was also helped by the fact that politically he was a man of the center. He was an internationalist in foreign affairs, a moderate on civil rights and social questions and a conservative on fiscal matters.

His standing in the government was evident in 1963 when President Lyndon B. Johnson named him to the commission that investigated the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. In 1965, he was elected minority leader of the House, the top Republican position in a Congress controlled by Democrats. He held that post until he became vice president.

When he left the White House, Ford wrote his memoirs, established his presidential library at the University of Michigan, served on the boards of various corporations, gave hundreds of speeches, played golf and divided his time between homes in Rancho Mirage and Beaver Creek.

He apparently had no second thoughts about his career. "Once I determine to move, I seldom, if ever, fret," he wrote in his memoirs. It was one of the most notable aspects of his character, and he never wavered from it.

In 1983, he told The Post that losing to Carter "truly hurt" but that he had been "doing as good a job as possible under very difficult circumstances" and that he was not going to "sit around and cry about it."

Instead of complaining, Ford pitched in to help his party. In 1980 he campaigned hard for his old foe, Reagan, who decisively defeated Carter. "I'm a political realist," Ford told The Post in 2004 in looking back on that election. "You win some and you lose some, and you have to accept the responsibility to do what you think in the bigger perspective. I sure didn't want Jimmy Carter to be president again in 1980 because I was very sour on his performance as president."

In the late 1970s, the Ford family received expressions of respect and sympathy from all over the country when former first lady Betty Ford described her successful struggle with addiction to alcohol and prescription drugs and how her husband and children had convinced her that she needed help. The Betty Ford Clinic in Rancho Mirage was named in her honor and became one of the nation's leading centers for the treatment of substance abuse.

In 1981, at the request of President Reagan, Ford joined Nixon and Carter in representing the United States at the funeral of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. The three former chief executives flew to Cairo aboard Air Force One. Ford and Carter began a warm friendship during the flight.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton conferred on Ford the Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor. He also received the Congressional Medal of Honor. In 2000, when he was hospitalized after suffering minor strokes during the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia, there was an enormous outpouring of public affection and concern.

In "Years of Renewal," the third volume of his memoirs, which was published in 1999, Henry Kissinger, Ford's secretary of state, offered this assessment of the former president:

"With Ford, what one saw was what one got. Providence smiled on Americans when -- seemingly by happenstance -- it brought forward a president who embodied our nation's deepest and simplest values."

In a passage on present-day politics, Kissinger drew an implicit distinction between Ford and subsequent White House occupants.

"The modern politician is less interested in being a hero than a superstar," he wrote. "Heroes walk alone; stars derive their status from approbation. Heroes are defined by inner values, stars by consensus. When a candidate's views are forged in focus groups and ratified by television anchorpersons, insecurity and superficiality become congenital. Radicalism replaces liberalism, and populism masquerades as conservatism."

In Kissinger's view, Ford was a leader in the heroic mold.

Born Leslie Lynch King Jr. on July 14, 1913, in Omaha, the future president was the offspring of a brief, failed marriage between Leslie King, a wealthy Wyoming wool merchant, and Dorothy Gardner King. The Kings divorced the following January, and she returned to her parents' home in Grand Rapids.

Soon thereafter, Dorothy King married Gerald R. Ford, a young paint salesman she had met at an Episcopal church social. He formally adopted her child, who was renamed Gerald R. Ford Jr. The Fords subsequently had three other boys.

Both Grand Rapids and Gerald Ford's paint-selling business prospered in the first years of the marriage. TerHorst, the former press secretary turned biographer, recounts that Gerald Ford Sr. "owned a touring car and there was enough money to take Mrs. Ford and young Jerry to Florida for vacations."

Ford was athletic, outgoing and happy in his youth. He became an adequate student, an outstanding football player and an Eagle Scout. Later, when his father's business declined during the Depression, he tried to help by taking a $2-a-week lunch counter job.

In the custom of those years, he had not been told that he was an adopted child. He found out abruptly when his well-to-do father, on the way to Detroit to pick up a new Lincoln, dropped by the lunch counter where his son worked and told him.

Leslie King invited his son to spend the summer with him in Wyoming after he graduated from high school. Ford turned him down, but he was shocked by the discovery of his adoption.

As terHorst recounted in "Gerald Ford and the Future of the Presidency": "Inside Jerry Ford, the hurt was deep." He quoted Ford as saying: "I thought, 'Here I was, earning $2 a week and trying to get through school, my stepfather was having difficult times. Yet here was my real father, obviously doing quite well if he could pick up a new Lincoln.' "

This incident occurred in 1930, the year Ford turned 17 and was a senior at South High School in Grand Rapids. He was an all-city center on the South High football team, which won the state championship that year.

Ford's football prowess opened a window to college, and his coach and some alumni from the University of Michigan provided him with a scholarship and a job waiting tables. He was a benchwarmer behind an all-American center for two years, while Michigan won back-to-back Big Ten football championships.

Not until 1934, in his senior year, did Ford win a starting place on Michigan's football team. Then he was voted the most valuable player on a team that lost seven of eight games and was offered professional football contracts with the Green Bay Packers and Chicago Bears. But Ford said in his autobiography that he thought the law would be a better career.

Ford graduated from the university in 1935 with a B average. He accepted a $2,400-a-year offer to serve as boxing coach and assistant football coach at Yale University, meanwhile applying to Yale Law School. The law school turned him down in the belief that he would not be able to do well in his studies while coaching.

Ford was accepted on a trial basis in 1938 and did well enough in a couple of courses to be allowed to enroll full time. He graduated in 1941 in the upper third of his class with his best work in a course on legal ethics.

Returning to Grand Rapids, he founded a law practice with Philip A. Buchen, a fellow Michigan graduate who had been partly crippled by polio in childhood.

Already Ford was drawn to politics. He had become active in Grand Rapids the previous summer in the campaign of Republican presidential candidate Wendell Willkie, who went down under Franklin Roosevelt's third-term candidacy, but who carried Michigan. Ford's interest in Willkie revealed a consistent internationalist bent that was evident in all of his succeeding political conflicts.

The Willkie campaign also drew Ford into local Republican affairs, where he sided with a reform group known as the Home Front, which was seeking to break the power of an entrenched Republican boss.

Ford's budding political interests were interrupted by World War II. He joined the Navy and spent 47 months on active duty, two years of this time on the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Monterey, where he was once nearly swept over the side during a typhoon. He left the Navy in 1946 with the rank of lieutenant commander.

He resumed his legal career in Grand Rapids and became active in a variety of community projects, culminating in 1949 when the national Junior Chamber of Commerce selected him as one of the nation's "10 most outstanding young men."

The year of 1948, when President Harry S. Truman was confounding pollsters by winning an upset victory over Thomas Dewey, was a time of decision for Ford. He ran for the U.S. House of Representatives in what seemed to be a hopeless battle against the entrenched Republican conservative, Bartel J. Jonkman, of western Michigan's 5th congressional district.

Jonkman was of Dutch descent, and the Dutch were the largest single ethnic group in the district. He was considered an isolationist who opposed American involvement overseas in general and aid to Europe as proposed by President Truman under the European Recovery Plan in particular.

In retrospect, Ford seems to have been in tune with the changing times. American involvement in World War II had dissipated isolationist sentiment in the nation's heartland. The internationalist Willkie had done well in Michigan as early as 1940, and Sen. Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan, the senior Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, had dramatically shifted from an isolationist to an internationalist position during the war.

Vandenberg was a political opponent of Jonkman, the senior Republican on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, and he encouraged Ford's seemingly hopeless candidacy. Jonkman also was considered by some local Republicans to be spending too little time in his home district. Ford waged a vigorous handshaking campaign, aided by members of the reform group he sided with before the war. He had the support of the largest daily newspaper in the district, the pro-Vandenberg and anti-isolationist Grand Rapids Press.

In the September primary, Ford defeated Jonkman, 23,632 votes to 14,341. He won the general election with more than 60 percent of the votes, a feat he repeated in each of the following 12 elections.

Ford had proposed marriage in February 1948, to Elizabeth Bloomer Warren, a dancer and former model, and she had accepted. But the couple kept their plans secret out of concern that her background as a dancer and a divorced woman would have an adverse effect in the Republican primary among Dutch Calvinist voters in the district.

They were married Oct. 15, 1948, in Grace Episcopal Church, which Ford attended. They had four children, Michael Gerald Ford, John Gardner Ford, Steven Meigs Ford and Susan Ford Vance.

In Washington, Ford occupied an office in what is now the Cannon House Office Building. Next door was a Democrat from Massachusetts named John F. Kennedy. Ford also formed a friendship with Richard Nixon, then a second-term House member from California.

Ford quickly established himself as a district-service congressman who answered every letter and made himself available to visitors from his state. He staffed a trailer with aides who traveled from town to town in his district. He won political points by taking stands that struck responsive chords among his constituents, such as a 1953 appeal that the United States admit 50,000 Dutch immigrants after disastrous floods in the Netherlands.

Constituent service also was the watchword of Vandenberg, whom Ford admired almost reverentially and who in turn considered the new congressman something of a protege. When Vandenberg died in 1952, Ford briefly considered running for his seat but decided to stay in the House.

Ford became as popular among his House colleagues as he had been in Grand Rapids. He found time to golf, swim and ski, and he was accepted into the Chowder and Marching Society, a group of House members that has always welcomed former athletes.

The new congressman was named to the assignment of his choice, the politically helpful House Public Works Committee, in his first term. In his second term, in 1951, he was appointed to the influential House Appropriations Committee.

On foreign policy, Ford remained true to the issues he had espoused in his first campaign. He supported President Truman's "Point Four" program for aiding underdeveloped countries, and he consistently favored foreign military aid. His internationalism displayed itself again in candidate preferences, and he supported the nomination of Dwight D. Eisenhower at a time when Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio was favored by most Midwestern Republicans in Congress.

On domestic issues, Ford was an orthodox Republican. He voted against public housing, against the minimum wage and against repeal of the "right-to-work law" provision of the Taft-Hartley Act.

On civil rights issues, he was considered a Republican moderate during most of his career. He voted against the poll tax, a device to keep the poor -- especially blacks -- from voting, and he voted for the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. But he also opposed school busing to achieve racial integration, a position that disappointed members of the Congressional Black Caucus, all of them Democrats estranged from the policies of the Nixon administration. Only one member of the caucus, Rep. Andrew J. Young of Georgia, voted to confirm Ford as vice president.

Republican colleagues in the House considered him progressive on making the House a more responsive institution.

His first vote in Congress was in favor of changing House rules to make it easier to bring a bill up on the floor without clearance from the House Rules Committee.

During the two Eisenhower administrations, Ford gradually advanced toward House leadership. He held a senior position on the Appropriations Committee and played a growing role in GOP strategy councils. In a 1960 poll of Washington correspondents, Newsweek rated him second among the ablest members of Congress.

Ford's breakthrough into a major position of leadership occurred in 1963 when he was the candidate of a group of younger Republicans, slightly to their party's left of center, to challenge 67-year-old Charles B. Hoeven of Iowa for chairmanship of the House Republican Conference.

One of the public highlights of the Ford minority leadership was a weekly news conference with Sen. Everett M. Dirksen (R-Ill.), which quickly became know as the "Ev and Jerry Show." Ford lacked Dirksen's oratorical talents, and he sometimes found himself on the losing end of exchanges with the Illinois senator.

It was during this period of his career that Ford was on the receiving end of two well-publicized gibes from President Johnson. The president once suggested that Ford couldn't "chew gum and walk at the same time" and also commented that "there's nothing wrong with Gerald Ford except he played football too long without a helmet."

Ford incorporated the latter remark into some of his own speeches, correctly giving the original authorship to former Detroit Mayor Gerald Cavanaugh.

However, House colleagues on both sides of the aisle disputed the idea that Ford was less than bright. They pointed to his shrewd, effective leadership in the House and his mastery of such complexities as the defense budget.

Ford's accomplishments as a House leader were based not upon his public pronouncements but upon a talent for friendly persuasion attested to by many members on both sides of the aisle.

"It's the damnedest thing," said Rep. Joe Waggonner (D-La.). "Jerry just puts his arm around a colleague or looks him in the eye, says, 'I need your vote,' and gets it."

Most of Ford's public declarations in the mid-1960s were orthodox, oppositionist rhetoric, peppered with football expressions of "end runs" and "team play." He said the Johnson administration was taking the country into "frustration and failure, bafflement and boredom." Once he said, "If Lincoln were alive today, he'd be spinning in his grave."

Occasionally, however, Ford was capable of defining his own political moderation in words that set him apart from the Nixon administration, which he was soon to defend.

In a speech at Southern Methodist University on Nov. 8, 1968, he said: "The higher ground of moderation with unselfish unity is not only common horse sense for a political party, it is also representative of the people and in keeping with the underlying genius of the American political system."

In 1970, Ford was accused of abandoning the high ground of American politics when he launched an effort to impeach William O. Douglas, the liberal associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. In the course of the incident, he offered a definition -- much quoted during the Clinton years -- of what constitutes an impeachable offense.

Ostensibly, it was Ford's idea to impeach Douglas because of the appearance of excerpts of a book by the jurist in the Evergreen Review alongside material that Ford said was pornographic. However, after he became president, Ford admitted he had been helped by John N. Mitchell, the attorney general in the first Nixon administration, who was angry about Senate rejection of two of Nixon's Supreme Court nominees.

The charges presented by Ford were primarily political and made numerous references to Douglas's alleged "liberal" or "leftist" beliefs. Responding to congressional critics who said that these charges had nothing whatever to do with judicial misconduct, Ford said on April 15, 1970:

"What, then, is an impeachable offense? The only honest answer is that an impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history."

The impeachment resolution was shunted to a House Judiciary subcommittee, which found no grounds for taking action.

Ford's consistent advocacy of military preparedness and his internationalism made him an early supporter of the Vietnam War. When President Johnson sent a half-million troops to Vietnam in 1965, Ford emerged as a partisan critic who said the United States should take sterner measures, such as the bombing of North Vietnam and a naval blockade, in an effort to end the conflict.

"It is President Johnson's war, because the president plays everything close to the vest," Ford said on June 18, 1966. "He has an unhealthy passion for secrecy."

The use of the phrase "Johnson's war" brought Ford a rebuke from some Republicans, among them his fellow minority leader, Sen. Dirksen.

Ford served as permanent chairman of the 1968 Republican Convention, which nominated Nixon for president. When Nixon became president, Ford loyally supported his Vietnam policy, including the incursions into Laos and Cambodia and the bombing of North Vietnam. He later gave Nixon full credit for withdrawing U.S. troops from the war.

The new Nixon administration changed Ford's role from leader of the usually loyal opposition to outspoken advocate of the Republican president.

Ford's loyalty was rewarded after Agnew's resignation when Nixon nominated him for the vice presidency. Ford was the second choice after former secretary of the treasury John B. Connally, but Nixon was persuaded by various Republicans that Congress would not confirm Connally, a former Democrat.

Ford's nomination was the first made under the 25th Amendment, and it touched off a detailed inquiry into Ford's background and financial affairs by the two congressional judiciary committees.

He was confirmed by a 92-to-3 vote in the Senate and by a 387-to-35 vote in the House. Ford spent the better part of the next 10 months trying to defend Nixon on the Watergate issue, while at the same time condemning the practices of political espionage, lying and obstruction of justice uncovered in the Watergate scandal.

While he never criticized Nixon personally, he tried on several occasions to distance himself from the Nixon White House, most noticeably on March 31, 1974, when he told a Midwestern Republican conference in Chicago that the party must "learn the lessons of Watergate."

But it was not until the weekend before Nixon's resignation that Ford stopped proclaiming belief in Nixon's personal innocence. And it was not until the day before Nixon bade farewell to his high office in a nationally televised speech that Ford actually assembled a transition team.

In the aftermath of the pardon, Ford's political vulnerability was evident in his efforts to deal with Vietnam and its legacy.

He surprised many Americans by unveiling, in a speech to a Veterans of Foreign Wars convention, a conditional-amnesty plan for Vietnam-era draft evaders and deserters. The proposal drew a swarm of critics. Veterans groups opposed any amnesty program at all, while organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union called for unconditional amnesty. Of the estimated 100,000 draft evaders, only about 20,000 took advantage of the program. Although U.S. combat troops had been withdrawn by the time Ford took office, the president proposed an increase in aid for the South Vietnamese government to help it resist what was expected to be a major effort by the North Vietnamese communists to drive it out of the country.

There was little support for this in the new Congress. Early in 1975, it rejected Ford's proposals, turning a deaf ear to arguments that Washington had to stand by its beleaguered ally to maintain its credibility in world affairs.

The communist offensive began in April 1975, and Ford ordered the small remaining contingent of U.S. embassy and security personnel to leave. The final evacuation produced painful pictures of Americans in retreat -- officials scrambling to get aboard helicopters while Marines held back crowds of Vietnamese who had loyally supported the United States.

On April 23, 1975, in a speech at Tulane University, Ford announced that the war in Vietnam was "finished as far as America is concerned."

A week later, Saigon fell to the communists and the long war was over.

Ford later came to the view that U.S. policy in Vietnam was mistaken. He blamed this on an unthinking inheritance of French colonial policy. "The French had the wrong policy, and we inherited it, and our State Department was not smart enough to realize that we should have been more objective about our policy in Vietnam," Ford said in the 2004 interview with The Post. Asked if the United States should have withdrawn sooner than it did, he said: "Absolutely, in retrospect. Now, I wasn't strong enough to make that decision while I was in the White House but in reflection, there is no question."

Ford continued the Nixon policy of using Kissinger as a mediator between Israel and the Arab states in the Middle East. An agreement signed in September 1975, halted fighting between Israel and Egypt.

In the previous month, Ford had traveled to Helsinki to sign an accord that recognized the existing frontiers between states, including the border between East and West Germany. This implicitly recognized Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. In return, Moscow agreed to respect basic human rights and to ease restrictions on the free exchange of information and on emigration and travel within the Soviet Union.

Ford was criticized for signing the Helsinki Accords at a time when the press was reporting numerous human rights violations in the Soviet Union. But the president said in his autobiography, "A Time to Heal" (1979), he regarded the agreement as "a real victory for our foreign policy" because the Soviets had conceded that national borders could be changed by peaceful means.

But it was the domestic economy that proved the touchstone of Ford's presidency. The problems included inflation, rising unemployment -- it passed 9 percent, the highest level since the Great Depression -- and skyrocketing energy costs.

Soon after taking office, Ford said inflation was "public enemy No. 1." To fight it, he vetoed more than 50 spending bills. He also announced a 32-point program for fighting it, which he called "WIN," an acronym for "Whip Inflation Now."

Congress declined to enact most of Ford's anti-inflation proposals, however, and the WIN program was overtaken by the events of deepening recession. In January 1975, the president all but declared a ceasefire in his war on inflation and turned his attention to growing unemployment and sinking productivity.

In one of the most candid State of the Union messages ever presented to Congress, Ford in 1975 said:

"I must say to you that the state of the union is not good. Millions of Americans are out of work. Recession and inflation are eroding the money of millions more. Prices are too high and sales are too slow."

Ford followed this message with a budget proposal that predicted long-term unemployment and massive deficits. His essential answer to what he conceived as the twin problems of the economy and the energy crisis was a quick tax rebate to stimulate the economy and oil tariff increases to lessen American dependence on foreign oil.

Despite the seriousness and the variety of the problems that confronted him, Ford maintained his even-tempered composure and his optimism. He met frequently with a wide range of legislators, businessmen, labor officials, heads of state, reporters and other visitors.

He knew that his chances of winning a full term in 1976 were not good, but he approached it in the spirit of Harry S. Truman, whose bust he placed next to his desk in the Oval Office.

Truman, Ford used to say, "had guts, he was plain-talking, he had no illusions about being a great intellectual, but he seemed to make the right decisions."

Many would say the same of Gerald Rudolph Ford.

Officials Prepare for Ford's Body to Lie in State, Funeral Services President Ford, Presidential Museum And Library

Officials Prepare for Ford's Body to Lie in State, Funeral Services President Ford, Presidential Museum And Library~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This came as no surprise but it's still a shock when we lose one of our President's, especially one of this caliber. What a great man. President Ford will be greatly missed. I'm sure President Reagan is sharing his jelly beans with him now :-)